PSA: ChatGPT is the trailer, not the movie

March 02, 2023Authored by Casey Flaherty, Baretz+Brunelle partner and LexFusion co-founder

To Whom It May Concern,

You have been provided this link because someone believes it may help.

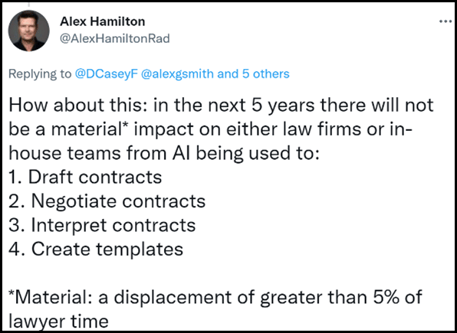

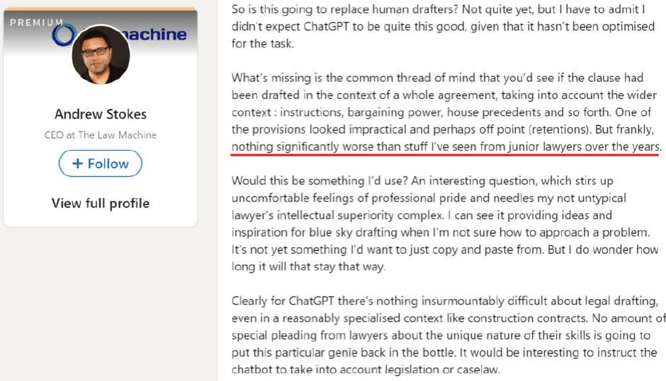

You may be new to this topic. If so, welcome! Alternatively, you may have contributed to the unhealthy preoccupation with ChatGPT. This does not mean you've said anything factually inaccurate. But you are reinforcing the unhelpful narrative that ChatGPT is the proper point of emphasis—a monomania reflected in articles like Chat GPT for Contract Drafting: AI v. Templates and tweets like:

It's fine. It happens. In fact, it happens a lot these days. Hence the post. Please do not be offended. The person who directed you here is only trying to advance the discourse. This is all rather new. We're all learning together.

The objective is to raise baseline awareness so we can engage in more productive conversations. The subsequent post is long. But the introductory synopsis is mercifully brief:

- ChatGPT is exciting. But ChatGPT is also explicitly a preview of progress with no source of truth.

- ChatGPT is an application of GPT-3.5, a transformer-based large language model ("LLM"). GPT-3.5 is a raw "foundation model" from Microsoft-backed OpenAI. Many other companies, like Google and Meta, are also investing heavily in foundation models. ChatGPT is one application of one foundation model.

- LLMs like GPT 3.5 can produce impressive results. But, in their raw form, they are not intended to be fit-to-purpose for many tasks, especially in highly specialized domains with little tolerance for error—i.e., there is no reason to expect raw foundation models to generate high-quality legal opinions or contracts without complementary efforts to optimize for those outputs.

- In particular, with no source of truth, LLMs are prone to hallucination, confabulation, stochastic parroting, and generally making shit up, among many other pitfalls. This can be remedied by combining LLMs with sources of truth—e.g., a caselaw database or template library—through methods like retrieval-augmented generation.

- We already have real-world examples of LLMs being enriched through (i) domain-specific data sets, (ii) tuning, including reinforced learning from human feedback, and (iii) integration into complementary systems that introduce sources of truth to successfully augment human expertise in areas like law, medicine, and software development. A myopic focus on ChatGPT ignores these examples and arbitrarily limits the conversation in unproductive ways.

- We also have real-world examples of failed attempts to leverage LLMs, as well as different applications of the same LLM to the same problem set with material differences in performance level. A powerful LLM is not sufficient. The complementary data, tuning, and tech are often necessary. Be wary of magic premised on the mere presence of an LLM.

- Despite the understandable focus on "Generative AI," the usefulness of LLMs is not limited to generation. LLM-powered applications can perform data extraction, collation, structuring, search, translation, etc. These lay the groundwork for generation but need not be generative to deliver value.

- LLMs will continue to advance at a rapid pace, and there will be many attempts at applying LLMs to legal. Some applications will be bad. Some applications will be good. Cutting through the hype and properly assessing these applications will require work.

- It remains TBD (and fascinating and, for some, frightening) how and when LLMs will prove most applicable to augmenting legal work. The road to product is long, and we are at the front end of an accelerating growth curve.

- No one knows what will happen. We're all making bets. Abstention is a bet.

- Be prepared for unrealized hype, unforced errors, excruciating debates, exciting experimentation, and (the author is betting) real progress. Things will get weird.

- "AI will replace all lawyers" is almost certainly an embarrassingly bad take for the foreseeable future. But "AI will not displace any lawyers because of what ChatGPT currently does poorly" is undoubtedly a bad take today.

The truly TLDR summary: too many lawyers are worried about ChatGPT when they should be excited about CoCounsel. Those are the bones. If you need more, the meat follows.

The author is an LLM bull. But being an LLM bear is totally fine. I take strong positions on the potential application of LLMs to legal service delivery, including:

- This will be done BY you or this will be done TO you. This is happening. I consider these seismic advances to be more akin to email and mobile than some narrow progress within legal tech that lawyers can choose to ignore. Shifts in the general operating environment will make incorporation of this rapidly maturing technology a necessity and require changing many of the ways we currently work.

- In 2023, AI will be capable of producing a first draft of a legal opinion or contract superior to the output of 90% of junior lawyers. "Junior" is responsible for some heavy lifting in that statement. And capacity is not the same as fully productized and widely available—the road to product is long. Yet technical thresholds will be surpassed in ways that should force us to fundamentally rethink workflows, staffing, and training.

A primary source of my confidence is previews from co-conspirators at law departments, law firms, and legaltech companies working on LLM use cases that are not yet public. Some of these friends mock me for not having the courage of my convictions. Compared to them, my predictions are downright conservative.

One senior in-house friend said to me this week, "People will start scrambling. Their place in the value chain is about to be markedly less secure." Another put a similar sentiment in more colorful terms, "The boat is leaving the dock. You can be on it, or you can swim."

I am a relative LLM bull. There are, however, legitimate reasons to be an LLM bear. Many peers I respect default to doubt on this subject. You will find smart, credentialed people on both sides of the debate. This post is not an attempt at persuasion on the inevitability of LLMs, let alone the robot lawyer event horizon.

The LLM doubters may turn out to be right. No one knows. So we place bets. Indeed, after including the "90% of junior lawyers?" statement above in the LexFusion Year in Review piece on Legal Evolution, I ended up in a friendly wager with the great Alex Hamilton.

Alex set the parameters of the bet: AI displacing 5% of what lawyers do in contracting within 5 years. I would have taken 3 years and 30% displacement to make it more interesting.

Yet, as bullish as I am (and as much crow as I will eat if LLMs turn out to be Watson 2.0), the prediction I have highest confidence in is rather bearish:

- There will be a flood of garbage products claiming to deliver AI magic. This is a near certainty. Regardless of how useful well-crafted applications powered by LLMs may prove, there will be many applications that are far from well-crafted and are merely attempting to ride the hype train.

We're already seeing this with ChatGPT.

ChatGPT is awesome. If we assess ChatGPT on its own merits, ChatGPT absolutely delivers.

ChatGPT is a "preview of progress." So explained Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, the Microsoft-backed startup behind ChatGPT.

The November 30, 2022 release notes for ChatGPT are not cryptic:

- ChatGPT was being released as a "research preview"

- ChatGPT has "no source of truth"

- ChatGPT therefore "sometimes writes plausible-sounding but incorrect or nonsensical answers"

- ChatGPT "is sensitive to tweaks to the input phrasing"

- ChatGPT has issues that "arise from biases in the training data"

- ChatGPT tends to "guess what the user intended" rather than "ask clarifying questions"

- ChatGPT "will sometimes respond to harmful instructions or exhibit biased behavior"

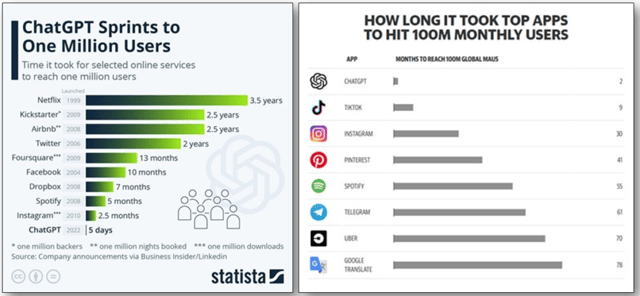

ChatGPT was novel because of the Chat aspect. ChatGPT offers a conversational user interface layered on top of one of OpenAI's foundation models, GPT-3.5. ChatGPT proved an immediate sensation, reaching one million users in five days and one-hundred million users within two months.

The hype cycle commenced. The interest drove hype. The hype drove interest. Mass tinkering uncovered all manner of tantalizing use cases. BigLaw partners who have been practicing for 40-years were entering prompts and rightly finding some (not all) "results were nothing short of amazing—especially with the speed. Mere seconds which even the most knowledgeable expert could not hope to match."

Posts, articles, and news coverage on ChatGPT approached ubiquity. Suddenly, everywhere you looked, someone like Larry Summers was signal boosting themselves with pronouncements like "ChatGPT is a development on par with the printing press, electricity and even the wheel and fire."

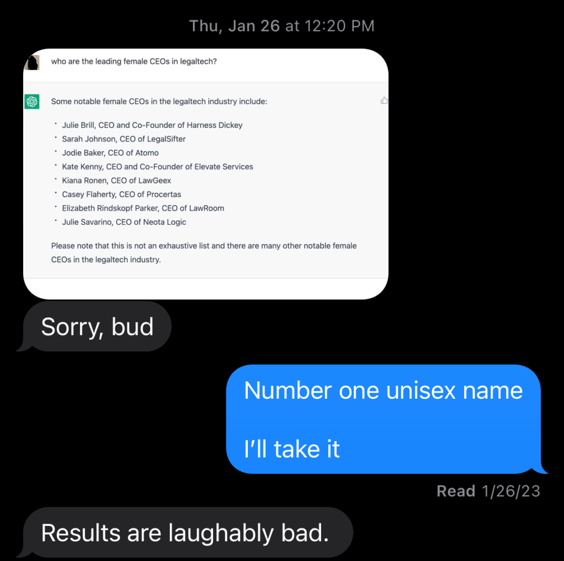

Invariably, the backlash followed. Specifically, many legal denizens became avid hate prompters. Hate prompting entails a domain expert inputting a ChatGPT query and then publicly bashing the output. A benign example is a beloved friend texting me ChatGPT's list of notable female CEOs, which includes yours truly (never been a CEO; never identified as a woman) and concluding the "results are laughably bad."

Those results were laughably bad. Hate prompts have produced similarly ludicrous results when tasking ChatGPT with all manner of legal work.

But, again, ChatGPT was not built to do any of that well, let alone perfectly. ChatGPT merits experimentation, and people have every reason to explore the possibilities it might presage for incorporating foundation models into fit-to-purpose products. But we should also learn enough about what ChatGPT is, and is not, to avoid being shocked that a raw model released as a research preview with no source of truth sometimes produces plausible sounding but incorrect or nonsensical answers, especially in highly specialized domains. They told us that Day One.

The hate prompters will say they are merely responding to the hypists. I submit both are guilty of injecting too much noise into a vital conversation by artificially narrowing the debate to what ChatGPT can and cannot do today. I attempted to address this noise in a two-part series for Legaltech News entitled "The Focus on ChatGPT Is Missing the Forest for the Tree" (Part 1, Part 2). This post is a recitation and extension of that series.

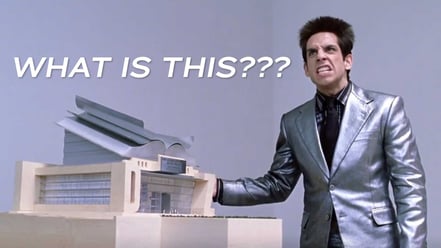

In Part 1, I suggested those fixated on ChatGPT—rather than appropriately treating it as a preview of progress—are re-enacting the eponymous Zoolander's tantrum upon being presented a scale model for the "Derek Zoolander Center for Kids Who Can't Read Good and Who Wanna Learn to Do Other Stuff Good Too." Lacking any capacity for abstraction, the face-and-body boy confuses the miniature preview for the thing itself, summarily rejecting it, "What is this? A center for ants?"... How can we be expected to teach children to learn how to read... if they can't even fit inside the building?"

Invoking Zoolander failed to elevate the discourse. The avalanche continued.

About a week after my series, the usually informed and informative Jack Shepherd published Chat GPT for Contract Drafting: AI v. Templates, which treats ChatGPT as a stand-in for AI and then AI as somehow incompatible with templates (it is all there in the title, but you can read the piece for yourself). This was followed a few days later by So How Good is ChatGPT at Drafting Contracts?, which, to be fair, offers all the correct caveats in its conclusion. The cacophony resulted in webinars on Legal Considerations for ChatGPT in Law Firms and articles like As More Law Firms Leverage ChatGPT, Few Have Internal Policies Regarding Its Use—which were necessary but also serve to reinforce the monomania.

When Brookings is publishing acontextual tracts like Building Guardrails for ChatGPT, we should forgive casual observers for thinking ChatGPT is the correct focal point. But once you stop being a casual observer and choose to engage in the discourse, you assume a duty to advance it.

So here we are, as I live my motto: if you find yourself screaming into the void, just scream louder (and with a much higher word count).

I am not a female CEO nor an LLM expert. Since I have the audacity to label Jack and the hate prompters as Zoolanders, I must confess I am more Hansel than JP Prewitt. My technical knowledge does not extend much beyond "the files are IN the computer." (h/t Stephanie Wilkins)

I will not embarrass myself trying to explain LLMs. I commend this article from the famed Stephen Wolfram, as well as this video from the soon-to-be-famed Jacob Beckerman, founder of Macro who did his thesis work in natural language processing.

I will not pretend to have a comprehensive grasp on the players in the space. I suggest this article from Andreesen Horowitz, who, as it happens, just led a $9.3M seed round in Macro (bias/brag alert: Macro is a LexFusion member).

Indeed, while I have endeavored to slowly educate myself, I am not the least bit qualified to educate others on tokens, alignment, retrieval augmented generation (RAG), DocPrompting, reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), edge models, zero-shot reasoning, multimodal chain-of-thought reasoning, fine tuning, prompt tuning, prompt engineering, etc.

My super basic take is LLMs recently passed a threshold with language that computers long ago crossed with numbers. This is the convergence of decades of cumulative advances in AI architecture, computing power, and training-data availability. This time is different because LLMs have demonstrated unprecedented flexibility, including emergent abilities.

GPT is the abbreviation for "generative pre-trained transformer." These are foundation models because the pre-training creates the conditions for the models to be tailored to different domains and applications (WARNING: frequently, they still need to be tailored). Seemingly daily, there is yet another paper on a more efficient way to tune models to tasks. This opens up a world of possibilities we're just starting to get a taste of with the likes of ChatGPT, AllSearch, CoCounsel, Copilot, Med-PaLM, Midjourney, and CICERO, among many others.

Like I said, it is a basic take, and you should look elsewhere for deep understanding.

But Richard Susskind did not need schematic understanding of SMTP, IMAP, POP, or MIME in 1996 to predict email would become the dominant form of communication between lawyers and clients. He merely needed to grasp the jobs email did and recognize that the rise of webmail clients built atop WYSIWYG editors would cross the usability tipping point Ray Tomlinson envisioned after he invented email in 1971.

Tomlinson worked in relative obscurity for decades. At the same time Tomlinson's contribution was finally receiving its just due, Susskind was being labeled "dangerous" and "possibly insane." Some lawyers called for Susskind to be banned from public speaking because he was "bringing the profession into disrepute" due to his willful ignorance of how email undermined client confidentiality. Less than a decade later, a lawyer was laughed out of court for claiming failure to check his email was "excusable neglect."

Susskind did not persuade lawyers to adopt email. Clients did. The world changed. Resistance was futile. But futility took time to become apparent and was the subject of furious, if mostly nonsensical, debate.

With ChatGPT, what was relatively obscure has become an extremely public conversation that dwarfs any previous AI hype cycle (even Watson). My thesis is you do not need a technical background to understand that limiting the terms of the attendant debate to ChatGPT is a disservice to the discourse.

LLM-powered applications are effective in legal. Casetext began experimenting with LLMs years ago to augment the editorial process some of us still call "Shepardizing" despite that trademark belonging to our friends at LexisNexis (another bias/brag alert: Casetext is also a LexFusion member).

The challenge with automating the analysis of subsequent treatment of a judicial decision is the linguistically nuanced ways a court might overturn, question, or reaffirm. Core to the appeal of LLMs is the capacity to handle linguistic nuance.

In the beginning, the LLMs did not work too well on legal text. Eventually, after being trained on massive amounts of legal language and refined through reinforced learning from human feedback, the models proved so adept that Casetext extended the technology to search.

Parallel Search represents the first true "conceptual search" for caselaw. While we've had "natural language" search for decades, it, at best, is the machine translating keywords into Boolean searches with some additional fuzzy logic and common synonyms. Conceptual search is different in kind, not just degree—identifying conceptual congruence despite no common keywords.

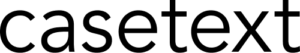

One of the many jokes I have stolen from Casetext co-founder Pablo Arredondo is that Parallel Search could have been called "partner search" because it is the realization of a dream/end of a nightmare. Pablo and I are both former litigators. Every litigation associate is intimately familiar with the terror of a partner exclaiming some variant of "I am sure there is a case that says X."

When searching for "X" does not produce the case that definitely exists, the associate begins the sometimes endless pursuit of typing in potential cognates of X. The associate is attempting to break out of the keyword prison to translate statement X into concepts. In grossly simplified terms, this is what the transformer-based neural networks underpinning Parallel Search have already accomplished—indexing the text of the entire common law in 768-dimensional vector space to surface similarities based on meaning rather than word selection (which is not say the machine "understands" meaning in the conscious sense, only that it is able identify parallel word clusters based on meaning instead of verbiage).

Parallel Search is excellent. But judicial decisions are not the only document type containing legal language. Casetext built AllSearch to extend the technology to any corpus of documents—e.g., contracts, brief banks, deposition transcripts, emails, prior art, your document management system, etc.

Who objects to better search for caselaw, contracts, or a DMS? Not every application needs to be totally transformative. Most won't be. Still, better is better. In some instances, the introduction and proper application of LLMs will simply result in a superior version of that which we already do.

Further, while Casetext has used GPT-3 to help rank judge-generated text, Parallel Search and AllSearch were developed entirely in-house. They are also not generative in nature—they only return actually existing caselaw or documents. All three points are critical to thinking through LLM-powered applications in legal:

- GPT 3.5, the LLM underpinning ChatGPT, is only one LLM. LLMs can incorporate or be enriched through domain specific data. There will be horses for courses.

- LLMs are compatible with sources of truth, like the common law or a document repository. Just because ChatGPT does not have a source of truth does not mean all LLM-powered applications will operate without one.

- Asking ChatGPT to generate items from scratch has been the most prominent form of experimentation. But LLMs have many use cases beyond blank-page generation, including search, synthesis, summarization, translation, collation, categorization, and annotation.

Parallel Search and AllSearch are not generative. But CoCounsel is.

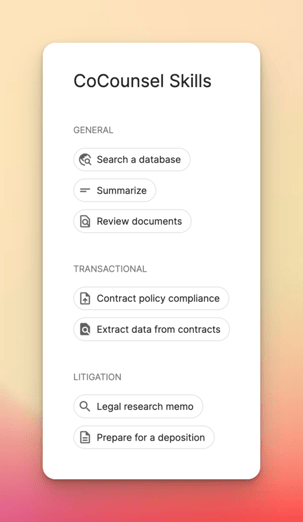

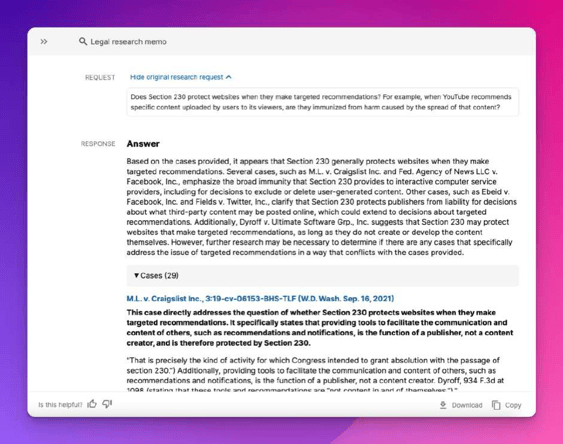

Properly-calibrated LLM-powered applications are effective in producing legal content. Today, Casetext announced CoCounsel. From the press release:

Today, legal AI company Casetext unveiled CoCounsel, the first AI legal assistant. CoCounsel leverages the latest, most advanced large language model from OpenAI, which Casetext has customized for legal practice, to expertly perform the skills most valuable to legal professionals...

CoCounsel introduces a groundbreaking way of interacting with legal technology. For the first time, lawyers can reliably delegate substantive, complex work to an AI assistant—just as they would to a legal professional—and trust the results...

CoCounsel can perform substantive tasks such as legal research, document review, and contract analysis more quickly and accurately than ever before possible. Most importantly, CoCounsel produces results lawyers can rely on for professional use and keeps customers'—and their clients'—data private and secure.

To tailor general AI technology for the demands of legal practice, Casetext established a robust trust and reliability program managed by a dedicated team of AI engineers and experienced litigation and transactional attorneys. Casetext's Trust Team, which has run every legal skill on the platform through thousands of internal tests, has spent nearly 4,000 hours training and fine-tuning CoCounsel's output based on over 30,000 legal questions. Then, all CoCounsel applications were used extensively by a group of beta testers composed of over four hundred attorneys from elite boutique and global law firms, in-house legal departments, and legal aid organizations, before being deployed. These lawyers and legal professionals have already used CoCounsel more than 50,000 times in their day-to-day work.

In short, the reliability concerns about ChatGPT are both legitimate and addressable. As I understand it (and, if I am wrong, Pablo will correct me once he's done making jokes on MSNBC), CoCounsel incorporates a specialized variant of retrieval augmented generation(RAG).

“RAG has an intermediate component that retrieves contextual documents from an external knowledge base.” While foundation models are probabilistic, not deterministic—which is why they hallucinate—we can still pair them with deterministic systems (or, more precisely, combine parametric memory with non-parametric memory). Indeed, the analogy used in the RAG research should be strikingly familiar. RAG combines "the flexibility of the 'closed-book' or parametric-only approach with the performance of 'open-book' or retrieval-based methods."

RAG is well suited to knowledge-intensive tasks because it is a method for incorporating sources of truth. We can, for example, limit operations to a pre-vetted knowledge base like the common law or a library of approved templates. In addition, "besides a textual answer to a given query they provide provenance items retrieved from an updateable knowledge base." Provenance means the output cites, and can often link to, its sources. Exactly what lawyers would expect for many forms of output (e.g., briefs, memos, summaries), whether generated by humans or machines.

For example, below is CoCounsel's output of a legal research memo followed by links to, summaries of, and relevant quotes from all the cited cases (generated in less time than it would take most lawyers to find a single relevant case).

LLM-powered applications have proven effective in producing content in other specialized domains. Lawyers will not be alone in using LLM-powered applications like CoCounsel to expeditiously generate quality, domain-specific content. Even before ChatGPT, Microsoft and OpenAI were being sued for $9 billion for Copilot.

ChatGPT released on November 30. On November 3, Microsoft, OpenAI, and GitHub (a Microsoft subsidiary) were named in a class action alleging violations of the open-source licenses under which creators post on GitHub, a code hosting service for developers worldwide. A second class action was filed on November 10.

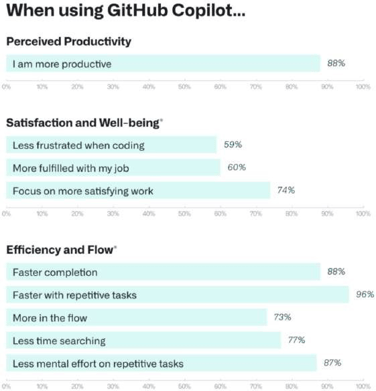

The lawsuits center on GitHub Copilot, an AI pair programmer that makes developers 55% faster. The tool suggests whole lines of code or even entire functions right inside the code editor, as opposed to the human developer searching GitHub separately to find a solution (think an associate searching the DMS or knowledge bank for a specific clause type or template). Copilot increases successful task completion (78% with, 70% without). The reduced friction of using Copilot also materially improves developer satisfaction: 74% are able to focus on more satisfying work because 96% are faster at repetitive tasks.

Github Copilot is powered by OpenAI Codex, which turns simple English instructions into over a dozen popular coding languages. Codex is a “descendent of GPT-3.” In addition to GPT-3, Codex’s training data contains “billions of lines of source code from publicly available sources, including code in public GitHub repositories.” That domain-specific fine-tuning is the basis of the lawsuits.

The vast majority of GitHub’s 28 million public repositories are covered by open-source licenses that require attribution of the author’s name and copyright. Among several claims at issue is the assertion that using the repositories for training violates the licenses.

I offer no opinion on the merit of the lawsuits. But this wave will, like blockchain/crypto, produce all manner of work for lawyers (e.g., the AI art generator lawsuits). Lawsuits, in particular, tend to be a sign of something gone wrong (damages) or something going right (where is my cut?). Copilot sits in the latter category.

I expect the proliferation of LLMs to drive actual legal work. And I expect legal work to make use of applications powered by LLMs because combining LLMs with domain specific data (Github repositories) and complementary tech (integration directly into the coding environment) can deliver return on improved performance—the true measure of effectiveness; much better than the eternal question of whether a specific task is entirely automated, let alone whether a human job has been completely replaced.

The mere presence of an LLM does not make an application effective and can make it dangerous. Two weeks before OpenAI unleashed ChatGPT, Meta released Galactica as a public demo. Meta pulled Galactica down after only three days.

Galactica had ingested 48 million scientific articles, websites, textbooks, lecture notes, and encyclopedias to “store, combine and reason about scientific knowledge.” Galactica was expressly designed to generate scientific papers and Wikipedia-like summaries, complete with references and formulas. Unfortunately, Galactica had a bad habit. Galactica was not merely wrong on occasion. Galactica compulsively produced compelling fabrications. Galactica went so far as to invent studies to support erroneous conclusions only experts could identify as utter fantasy—just as only true legal tech dorks can glance at ChatGPT’s list of leading female CEOs and recognize it as hallucination. Galactica concocted junk science (and yet it was still nowhere near as bad as Tay).

The domain-specific data was not sufficient to stop Galactica from exhibiting some of the well-documented challenges of properly applying LLMs. A small collection of cautions, from misinformation to environmental catastrophe to Skynet:

-

Sustainable AI: Environmental Implications, Challenges and Opportunities

-

The race to understand the exhilarating, dangerous world of language AI

LLMs are not magic. But raw foundation models are skilled illusionists—producing plausible-sounding wrongness that only experts can identify as claptrap. The mere presence of an LLM, even when working with domain-specific data, does not mean an application will be fit to purpose.

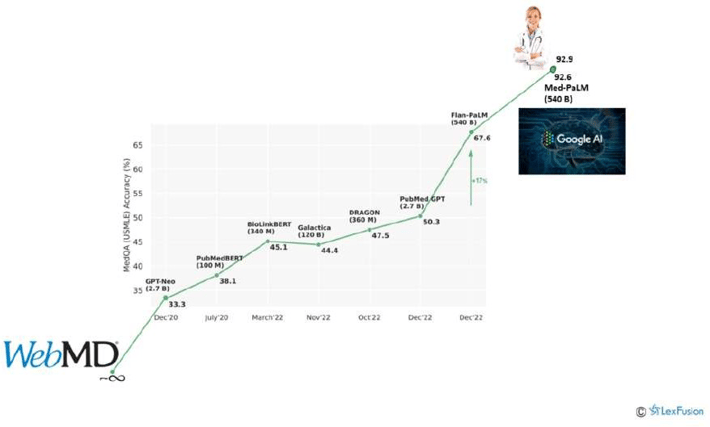

Two applications of the same LLM to same problem can have materially different performance levels depending on the complementary data, tech, and tuning. We’ve all typed symptoms into WebMD and come away wondering whether we have a cold or a terminal illness. Such pattern matching is something for which LLMs are, in theory, well suited. And now, too, in practice.

Google and DeepMind’s Med-PaLM suggests potential medical diagnoses based on identified symptoms. Results released at the beginning of January 2023 demonstrate Med-PaLM’s accuracy rate, as determined by a panel of human medical experts, is now 92.6%. Admittedly, that is not 100%. But it is nearing the accuracy of human clinicians presented with the same symptom sets. The human practitioners achieved 92.9% accuracy—0.3% better than Med-PaLM.

The model will only improve. It already has. As reflected in the chart, Med-PaLM predecessor Flan-PaLM only reached 61.9% accuracy. Both Med-PaLM and Flan-PaLM utilize the same foundation model: Pathways Language Model (PaLM). The difference in accuracy is the result of Med-PaLM’s “instruction prompt tuning.”

Again, I am not your huckleberry if you are looking to gain a nuanced understanding of multi-task instruction finetuning, CoT data, hard-soft hybrid prompt tuning, etc. The takeaway: there is nuance. The mere presence of an LLM is not sufficient. But, with the necessary complements, LLMs can produce some spectacular results even in highly specialized domains where minimizing error is mission critical—spectacular if we are fair in the standards we apply.

Despite the near parity with the clinicians, it is easy to imagine the uproar when a robot doctor suggests a potential misdiagnosis. We, however, should not lose sight of the fact that medical error is already the third leading cause of death.

Indeed, while Med-PaLM being 0.3% less accurate than the clinicians is the headline, it obscures the additional finding that Med-PaLM was also 0.7% less harmful. As adjudged by the same panel of experts, 6.5% of the clinicians’ answers were deemed to potentially contribute to negative consequences (i.e., make things worse), as compared to only 5.8% of Med-PaLM’s responses. In short, while the doctors were still marginally more affirmatively accurate, Med-PaLM delivered a higher percentage of answers that were either helpful or neutral—that is, answers that do no harm.

Actual human performance is a useful benchmark but human vs robot is a counterproductive framing. This is not a sin the researchers committed. The researchers’ thoughtfulness merits highlighting since the discourse in law is so prone to the false binary of human vs robot and then holding the machine to the standard of perfection, as if lawyers are infallible. From the Med-PaLM paper:

Recent advances in large language models (LLMs) offer an opportunity to rethink AI systems, with language as a tool for mediating human-AI interaction. LLMs are “foundation models,” large pre-trained AI systems that can be repurposed with minimal effort across numerous domains and diverse tasks. These expressive and interactive models offer great promise in their ability to learn generally useful representations from the knowledge encoded in medical corpora, at scale. There are several exciting potential applications of such models in medicine, including knowledge retrieval, clinical decision support, summarisation of key findings, triaging patients’ primary care concerns, and more.

However, the safety-critical nature of the domain necessitates thoughtful development of evaluation frameworks, enabling researchers to meaningfully measure progress and capture and mitigate potential harms. This is especially important for LLMs, since these models may produce generations misaligned with clinical and societal values. They may, for instance, hallucinate convincing medical misinformation or incorporate biases that could exacerbate health disparities.

To evaluate how well LLMs encode clinical knowledge and assess their potential in medicine, we consider medical question answering. This task is challenging: providing high-quality answers to medical questions requires comprehension of medical context, recall of appropriate medical knowledge, and reasoning with expert information.

The “exciting potential applications” the researchers cite involve the tech augmenting, not replacing, the human clinicians (i.e., an AI assistant like CoCounsel). Rather than human vs robot, the key question is whether human experts and the tech can be combined to drive superior patient outcomes than either alone. The same question applies in law with respect to client outcomes.

The models and the applications thereof will improve. Med-PaLM (Dec 2022) improved on Flan-PaLM (Oct 2021).

GPT-3.5 (March 2022) improved on GPT-3 (June 2020). GPT-3 is the successor to GPT-2 (Feb 2019), which succeeded GPT-1 (June 2018).

See here for an LLM Timeline.

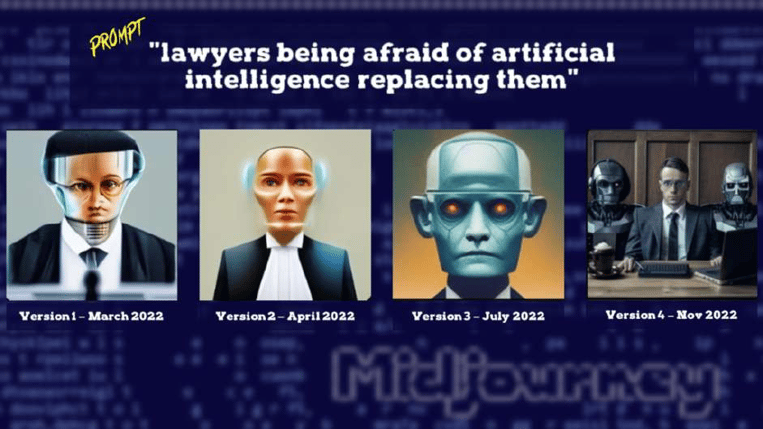

LLMs progress in a non-linear fashion (i.e., accelerating growth curve). My go-to example of LLM evolution is Midjourney, one of several new AI-art generators. The Midjourney Discord server allows users to run prompts through prior versions of the model. Below is the progression from Version 1 to Version 4 of machine-generated art responsive to the prompt “lawyers being afraid of artificial intelligence replacing them”:

I draw like the median four-year old. Even Version 1 of Midjourney is my superior in that regard. But Version 1’s output, while interesting, is useless. Version 4 not only achieves photorealistic draftsmanship but also a level of creativity that exceeds my, admittedly limited, imagination. Midjourney’s full journey from Version 1 to Version 4 was just under 8 months—basically, a school year. And that journey will continue, as will many others.

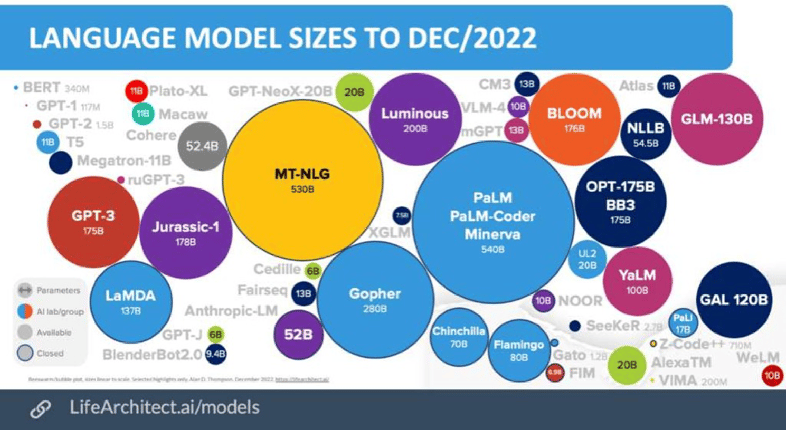

"From talking to OpenAI, GPT-4 will be about 100 trillion parameters." shared Andrew Feldman, founder and CEO of Cerebras, which builds computer systems for complex AI and deep learning, in a 2021 interview with Wired. 100 trillion parameters is astonishing and, apparently, ridiculous (for now).

Parameters are the independent values a model can change and optimize as it learns. While an oversimplification in a space where analogies are hard, one can think of parameters as the number of words a person knows. The more words, the more configurations thereof (i.e., independent values that can be optimized). But knowing words (memorizing the dictionary) does not mean we necessarily string the words together well (writing).

Recall that in the last section, both Flan-PaLM and Med-PaLM were powered by the same LLM. PaLM has 540 billion parameters. The latter outperformed the former due to instruction prompt tuning. The accompanying chart tracks how various LLMs performed on the same measure of diagnostic accuracy.

PubMed GPT (2.7B) wildly outperformed GPT-Neo (2.7B). BioLinkBert (340M) and DRAGON (360M) marginally outperformed the aforementioned Galactica (120B).

Indeed, because compute power is a major cost and constraint associated with foundation models, higher performance at a lower parameter count can be advantageous. For example, in introducing LLaMA last week, Meta explained, "Smaller, more performant models such as LLaMA enable others in the research community who don’t have access to large amounts of infrastructure to study these models, further democratizing access in this important, fast-changing field. Training smaller foundation models like LLaMA is desirable in the large language model space because it requires far less computing power and resources to test new approaches, validate others’ work, and explore new use cases."

Continuing the analogy. Someone with a talent for remembering words might excel at Scrabble but still be a mediocre author. And writing with a limited vocabulary—consider fabulous children’s books—can still be highly impactful. Parameter count is not everything. But parameter count is an indicium of a model’s power. And the bitter lesson of AI research is that, eventually, power dominates. That is, many believe, "model size is (almost) everything."

Thus, after ChatGPT previewed the prowess of GPT-3.5, the report that GPT-4 would have 100 trillion parameters went mainstream (it was repeated many places, including by me). GPT-3 has a parameter count of 175 billion. 100 trillion would be 570x larger.

We are not naturally disposed to appreciate such orders of magnitude. The best analogy I’ve encountered (many places; origin unknown) is that GPT-3 is throwing a garden party for 35 people while GPT-4 is renting out Madison Square Garden, capacity 20,000. That is, if GPT-3 is a high-school sophomore poorly cribbing from Wikipedia, GPT-4 might be a post-doc collating, parsing, and synthesizing the most complex and nuanced material in a subject area.

Except OpenAI’s Altman has already put that bombast to bed. In a recent interview, he explained “The GPT-4 rumor mill is a ridiculous thing. I don’t know where it all comes from. People are begging to be disappointed and they will be.”

Whatever the parameter count of GPT-4, disappointment is assured. But so, too, is progress. Imagination maintains a permanent lead on execution. But not keeping pace with the hype does not mean reality is standing still. Reality is racing forward on many fronts simultaneously.

GPT-3.5 is one of many foundational models on which huge bets are being placed. Galactica. PaLM. LLaMA. Midjourney. None are from OpenAI, let alone based on GPT-3.5, let alone ChatGPT.

ChatGPT is but one application of GPT-3.5. GPT-3.5 is but one of foundation model from OpenAI. OpenAI is but one company developing foundation models. ChatGPT is one application of one model from one company.

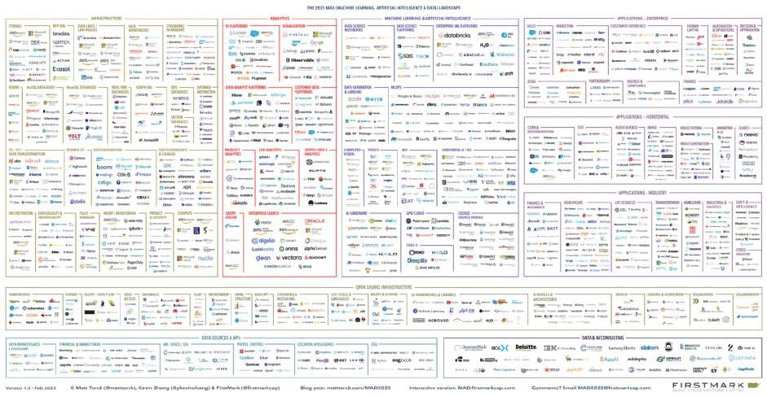

There are many models from many companies, including many from Big Tech. Megatron-Turing (Microsoft/Nvidia). LaMDA (Google). OPT (Meta). ERNIE (Baidu). Exaone (LG). Pangu Alpha (Huawei). Alexa Teacher (Amazon). These merely scratch the surface of a burgeoning landscape.

And not just Big Tech. In December 2022, NfX compiled a Generative Tech Open Source Market Map of over 450 startups who had already received over $12 billion in funding.

That compilation came before the ChatGPT floodgates had truly opened, including Microsoft announcing an investment of another $10 billion in OpenAI. Microsoft has already integrated GPT into Teams and Bing, with planned integrations into Word, PowerPoint, and Outlook. Maybe prematurely. It appears Microsoft accelerated this timeline to capitalize on the ChatGPT hype. Salesforce is not far behind.

Meanwhile, amidst layoffs, Google (well, Alphabet) has “doubled down” on AI. ChatGPT reportedly caused a “code red” at Google, who moved up the release of their ChatGPT-competitor Bard—the advertisement for which revealed a factual error, causing Google’s stock to plummet by $100 billion.

The race is on. We’re moving fast, and we’re breaking things.

The hype is extreme but not unprecedented. Expect the hype to be counterbalanced by many contrarian articles along the lines of The Clippy of AI: Why the Google Bard vs. Microsoft Bing war will flame out. Such articles are not entirely unfair. Who could forget Microsoft’s Azure Blockchain? (confession: me).

The current mania is most evocative of IBM’s Watson. Watson won Jeopardy! and was on its way to becoming a doctor, a lawyer, a chef, and smarter than people until it wasn’t. We’re now almost as far removed from peak Watson in 2011 as Watson was from 1997 when “in brisk and brutal fashion, the I.B.M. computer Deep Blue unseated humanity” by beating Gary Kasparov at chess in what was then termed “the brain’s last stand.”

The current mania is most evocative of IBM’s Watson. Watson won Jeopardy! and was on its way to becoming a doctor, a lawyer, a chef, and smarter than people until it wasn’t. We’re now almost as far removed from peak Watson in 2011 as Watson was from 1997 when “in brisk and brutal fashion, the I.B.M. computer Deep Blue unseated humanity” by beating Gary Kasparov at chess in what was then termed “the brain’s last stand.”

Deep Blue ascended 14 years after the New York Times explained to its readers in 1983 that before “today’s teen-agers finish college, computers will interpret changes in tax law and plan tax strategies for business.” That NYT declaration occurred 13 years after Life magazine proclaimed in 1970, “In from three to eight years we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being. I mean a machine that will be able to read Shakespeare, grease a car, play office politics, tell a joke, have a fight. At that point the machine will be able to educate itself with fantastic speed. In a few months it will be at genius level and a few months after that its powers will be incalculable.”

Deep Blue ascended 14 years after the New York Times explained to its readers in 1983 that before “today’s teen-agers finish college, computers will interpret changes in tax law and plan tax strategies for business.” That NYT declaration occurred 13 years after Life magazine proclaimed in 1970, “In from three to eight years we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being. I mean a machine that will be able to read Shakespeare, grease a car, play office politics, tell a joke, have a fight. At that point the machine will be able to educate itself with fantastic speed. In a few months it will be at genius level and a few months after that its powers will be incalculable.”

We are in for a torrential downpour of hype. Those who do not learn from the past are doomed to repeat it. We do not learn. Even if another AI Winter is not coming, much nonsense will be spoken. Maybe even by me.

As I said at the outset, I could be wrong in my bullishness re LLMs. I’ve been wrong before. Trying to operate at the center of the edge of legal innovation, I’ll be wrong again. I try to admit when I am wrong and examine why (e.g., here, here, here). Then again, I could be wrong in the other direction. I could be too conservative.

My primary aim here is to persuade those engaged in the discourse that limiting the conversation to ChatGPT is a disservice. I am not nearly as adamant about convincing you to share my sense that this time really is different. My bullishness is at odds with my historical bearishness, correctly lambasting robot magic silliness. The dominant gambling strategy in the near term is always that tomorrow will look much like today.

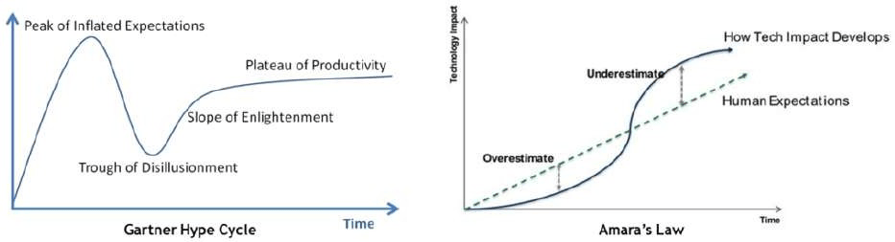

But, while I concede fallibility, I will not bite on the false binary. Like human vs robot, the reality vs hype fallacy misses all manner of fertile middle ground. With hype cycles, there is frequently something meaningful on the other side (the slope of enlightenment) even if the end state (productivity plateau) never lives up to the initial overreaction.

Hype cycles are not merely compatible with but directly incorporated into Amara’s Law: “we tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.”

Hype happens. FTX, Coinbase, Crypto.com and eToro spent a tidy $54 million to dominate the airwaves during last year’s “Crypto Bowl.” This year’s Super Bowl had zero advertisements related to cryptocurrency.

Crypto crashed. But crypto did not disappear. Moreover, the underlying blockchain technology has many use cases beyond crypto. Maybe blockchain will simply evaporate, like 3D TVs. More likely, it will remain a useful option in areas where it offers real advantages.

I never invested in crypto nor NFTs. I also do not dismiss those who did. It is an area where I am simply too ignorant—in the neutral, non-pejorative sense of lacking adequate information and understanding. It is ok to not have an opinion. Though, if I am being honest, it is probably also about being gun shy. Before I was of legal drinking age, I’d already lost some of the little money I had at the time on the Dot-com bubble, which took over its own Super Bowl back in the day:

The Crypto Bowl reminded many of the 2000 Super Bowl which has since been referred to as the “Dot-com Bowl”. That year 17 of 61 ads sold came from dot-com companies with a :30 ad costing $2.2 billion. Most, but not all, of those advertisers are either no longer in business or were acquired by another company. Perhaps the most famous (or infamous) ad was the sock-puppet from Pets.com singing “If you leave me now”. Pets.com declared bankruptcy just months after the Super Bowl. By comparison, the 1999 Super Bowl ran just two dot-com ads and in 2001 only one dot-com advertiser returned E*Trade.

Yes, the notorious, Amazon-backed Pets.com. In retrospect, the notion that merely owning a great domain was a sufficient basis for a viable business seems ludicrous. And yet.

And yet, while we don’t know how much PetSmart paid for the domain www.pets.com, we can ballpark how much PetSmart might demand to part with it today. Potentially more than the now-defunct business Pets.com’s peak valuation of $400 million given that the domain www.cars.com was recently valued at $872 million.

The Dot-com bubble was a bubble. It had all manner of excess, exuberance, and destabilizing animal spirits. But the core tenant that purely digital real estate can be extremely valuable has been borne out and no longer seems even the least bit controversial. It was, however, a somewhat bizarre concept at the time, despite the internet’s long period of percolation.

ARPANET delivered its first message from one computer to another on October 29, 1969 and changed over to TCP/IP on January 1, 1983, which is now considered the official birthday of the internet. The worldwide web, however, did not become publicly available until August 6, 1991. Five years later, in 1996, only 16% of US homes had internet access. Internet access would not hit the 75% penetration threshold until 2007, the year the iPhone was released (and was predicted to be “passé within 3 months”)

As recently as 2000, before the internet was a fact of life, it was still to some “a passing fad.” So, too, with personal computers, smartphones, social media, the cloud, and streaming. They all had their bubbles. They all reached a fever pitch of hype. None became everything that was promised or prognosticated. You can go back and easily find incredibly bad takes from well-credentialed people on both sides of every major development in technology, all of which took far longer to become mainstream than most of us remember.

As recently as 2000, before the internet was a fact of life, it was still to some “a passing fad.” So, too, with personal computers, smartphones, social media, the cloud, and streaming. They all had their bubbles. They all reached a fever pitch of hype. None became everything that was promised or prognosticated. You can go back and easily find incredibly bad takes from well-credentialed people on both sides of every major development in technology, all of which took far longer to become mainstream than most of us remember.

It is AI until it works, then it is just software. As we look to the infinite horizon, it is sometimes good to also reflect on just how far we’ve come. This is Sarah. Sarah gets it. We (including me) should be more like Sarah.

Then again, Thomson Reuters is still publishing hardcopy books (observes guy who still buys hardcopy books for personal reading). Even when it arrives, the future is not evenly distributed.

Some evidence I can offer in support of my bullishness is:

-

We’re just getting started

-

ChatGPT is already demonstrating general receptivity to LLM-powered applications

-

Parallel Search and AllSearch have already brought true conceptual search to legal

-

CoCounsel already demonstrates the potential of retrieval augmented generation in legal

-

Copilot is already making developers 55% faster

-

Med-PaLM is already near parity with clinicians on suggesting potential diagnoses

-

Midjourney is already producing photorealistic illustrations

-

CICERO already doubled the average human score, ranking in the top 10% of all participants, in the game Diplomacy

We haven’t covered the last one yet. In November 2022, the same month as the Galactica kerfuffle, Meta also released CICERO, the first AI agent to achieve human-level performance in the game Diplomacy:

Diplomacy, a complex game that requires extensive communication, has been recognized as a challenge for AI for at least fifty years. To win, a player must not only play strategically, but form alliances, negotiate, persuade, threaten, and occasionally deceive. It therefore presents challenges for AI that are go far beyond those faced either by systems that play games like Go and chess or by chatbots that engage in dialog in less complex settings.

The results themselves are, without question, genuinely impressive. Although the AI is not yet at or near world champion level, the system was able to integrate language with game play, in an online version of blitz Diplomacy, ranking within the top 10% of mixed crowd of professional and amateurs, with play and language use that were natural enough that only one human player suspected it of being a bot.

This wasn’t supposed to be possible, until it was:

Diplomacy has been viewed for decades as a near-impossible grand challenge in AI because it requires players to master the art of understanding other people’s motivations and perspectives; make complex plans and adjust strategies; and then use natural language to reach agreements with other people, convince them to form partnerships and alliances, and more. CICERO is so effective at using natural language to negotiate with people in Diplomacy that they often favored working with CICERO over other human participants.

Unlike games like Chess and Go, Diplomacy is a game about people rather than pieces. If an agent can't recognize that someone is likely bluffing or that another player would see a certain move as aggressive, it will quickly lose the game. Likewise, if it doesn't talk like a real person -- showing empathy, building relationships, and speaking knowledgeably about the game -- it won't find other players willing to work with it.

Computers keep hitting these benchmarks. Computers beat humans at checkers. Then chess. Then poker. Then Go (which us meat puppets have recaptured for a moment). Then Stratego. Now Diplomacy. And, despite some breathless media coverage about our new AI overlords, everyone pretty much yawned and proceeded on with their lives, just as we did with Watson and Deep Blue. It is a job-destroying robot until it is a dishwasher.

Meanwhile, our expectations ratchet up. Today, phone chargers have 48x the clock speed and 1.8x the programming space of the Apollo 11 Guidance Computer (AGC) that enabled humans to land on the moon in 1969. The AGC cost $285,000,000 in 2023 dollars and was bigger than a car. The supercomputer in your pocket—that connects you to almost 7 billion people and provides you instant access to most of the humanity’s accumulated knowledge—could guide more than 120,000,000 Apollo-era spacecraft to the moon, all at the same time (and that was the passé iPhone 6). Yet no one sits around in perpetual astonishment at these advances. Instead, we complain about battery life.

Pocket-sized computers that were once science fiction are now a necessity. But we are predisposed to focus on science that remains fiction. Where is my flying car?

Forget flying cars. We still don’t have self-driving cars.

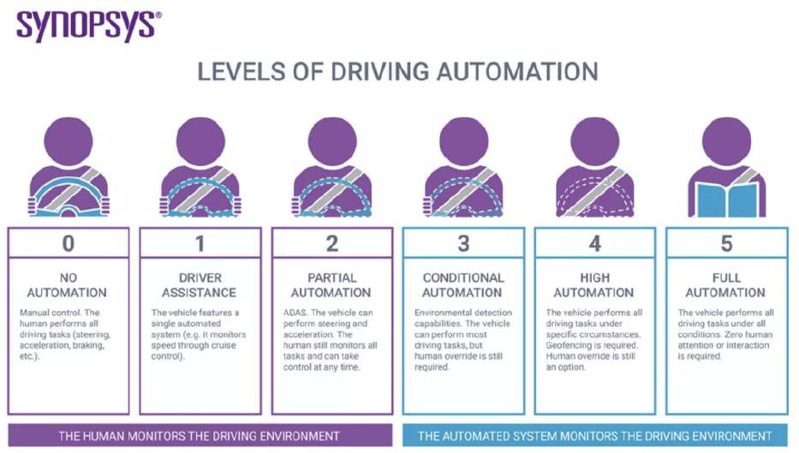

LLMs need not be everything, everywhere, all at once, immediately. The last-mile problems of fully autonomous vehicles have been known for decades. AVs have gone through many hype cycles over the last century, starting around 1925. We’re closer than we’ve ever been. And yet we’re still not there.

But where is “there?” Importantly, there has levels.

A useful conversation around AVs, or any form of automation, should proceed from the premise we do not need to achieve Level 5 to realize benefits. Nor need we accept as an article of faith that reaching Level 5 is, on net, beneficial. We are permitted to exercise judgment. In the case of AVs, applying standards like safety, environmental impact, and affordability. In the case of automating legal service delivery, benchmarks like outcomes, access, speed, and consistency.

I would submit that, despite some innovations being available for decades, many legal service delivery vehicles are gas guzzlers still operating without the equivalent of power steering or anti-lock brakes. Progressing to a current state where Level 1 automation (e.g., cruise control) is a standard feature therefore represents a material improvement. Better is better, even if it is not transformative.

Because of the allure of Level 5 transformation, our intuitions fail us on the impact of addressing low-end friction at Level 1. Improving a vehicle from 10 mpg to 20 mpg (2x, +10 mpg) conserves more gas than the leap from 20 mpg to 200 mpg (10x, +180 mpg). Improving lawyer throughput from 1 contract per hour to 2 contracts per hour (or any unit of legal production) saves more time than supercharging their throughput from 2 contracts per hour to 20 contracts per hour. Go ahead, check my math.

Because low-end friction is such an underappreciated problem, I’ll take it a step further. If all the LLM hype accomplished was to shift expectations such that the broader legal market started taking better advantage of document automation technology and basic knowledge management hygiene we’ve underutilized for decades, this would represent a marked improvement. I expect more. But a phase shift to better use of the tools we already have is still an upgrade on the status quo.

Imagine a scenario where the sole improvement attributable to the LLM is a chat-like interface embedded in Outlook, Teams, and Word. This merely initiates tried-and-true workflow and document automation (using any of 250+ tools already in the Bam! Legal Doc Auto Database). And we proceed from there.

I can hear some of my friends howling. They are vigorously pointing out we already have both chatbots and plug-ins that can initiate basic document automation, and these are listed in the database I just pointed to. They are correct. But we also landed a person on the moon before introducing the roller suitcase despite 5,000 years with the wheel—and, even then, the roller suitcase took decades to catch-on. Sometimes we need something to punctuate the equilibrium. I am positing that LLMs are that thing.

LLMs are not at war with boring. Hype can make boring cool. This brings me to the second reason articles like Chat GPT for Contract Drafting: AI v. Templates drive me to drink or respond at excruciating length (and, to be candid, sometimes do both simultaneously). AI and templates are completely compatible, again, because of retrieval augmented generation (RAG). But the broader point is you need not integrate LLMs into the actual document automation for the LLM to be the hook that results in greater use of document automation. Rather, the LLM might enhance the user interface (ChatGPT), subsequent drafting (Copilot), negotiation (CICERO), analysis (Med-PaLM), data extraction (AllSearch), etc.

Success should not be defined by whether LLMs teleport us from Level 0 to Level 5 automation instantaneously. Success is leveling up. LLMs increase my personal optimism as to what is possible and when. But even reflexive contrarians should not look this hype horse in the mouth.

We tend to move the goalposts. Jack, the author of Chat GPT for Contract Drafting: AI v. Templates and a peer I genuinely respect, has suggested to me on social media that I am misreading him. He has pointed out several times that he was limiting his analysis to whether ChatGPT could produce a contract superior to a carefully crafted template. I responded each time that this narrow focus was precisely the problem; he was missing the forest for one tree (and if you don’t understand why by now, I should have my keyboard impounded).

But consider the violent ratchet effect his analysis reflects. Six months ago, the idea of such a comparison would have struck most people as absurd. Asking a bot trained on general data from the internet (it does not maintain access to the data, nor have access to the internet) to draft a legal contract from scratch is wild. Yet here we are. And as soon as we got here, the bar was raised. The bar was raised not from (a) can the machine produce a contract from scratch? to (b) can the machine produce a first draft of contract sufficient for lawyer review? but to (c) can the machine produce a contract superior to an expert-curated template?

Today, the answer is No. It is supposed to be. But once some law firm, law department, or legal innovation company combines an LLM with proprietary data (existing templates, contract repository, curated clause bank, deal points database) and proper tuning to either generate templates or structure a workflow that achieves the same ends as automated templates, the bar will be raised yet again. The bar will likely become (d) can the machine produce a contract superior to an expert-curated template IF the expert is me and I had infinite time?

Fortunately, Ken Adams has already written the intellectually honest version of (d).

Ken combines intellectual ferocity with intellectual consistency. Ken does not discriminate. Ken holds everyone to the standards set in his A Manual of Style for Contract Drafting (the 5th edition is hot off the press). He’s torn into work product from the likes of Kirkland, Wachtell, and the Magic Circle—in addition to document assembly tools from DLA and Wilson Sonsini, not just Avvo and LegalZoom. Indeed, if you need a laugh break, take a moment to enjoy Ken’s many colorful descriptions of EDGAR, which serves as a vast repository of public companies’ material contracts. He’s referred to this massive archive of contracts from lawyers hired by large corporations as “the great compost heap” and “that great manure lagoon.”

Because Ken has concluded contracting is a terrible mess, he recognizes technology merely automates this dysfunction (e.g., here, here, here). Thus, Ken does not expect ChatGPT or similar systems to produce quality contracts because these would merely be “copy-and-paste by another name.” This is fair.

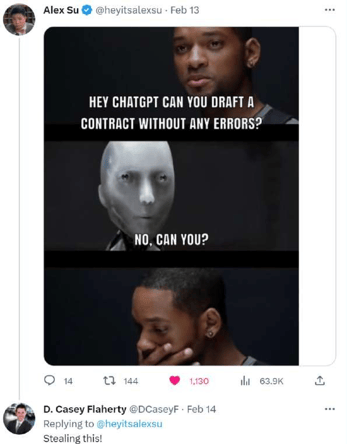

I was expressly echoing Ken in 2018 when I wrote How much of lawyering is being a copy-and-paste monkey?. For that post, I dug deep into the academic literature on the “problem of unreflective copying of precedent provisions” combined “with ad hoc edits to individual clauses” leading to “systematic inefficiencies” in a drafting process that “raises costs and risk to clients.” So much reading and so many words to argue that modern contract production is largely copy-and-paste, and this is bad. Then, in swift and brutal fashion, Alex Su expressed it far better in far fewer words:

As Ken concludes, “it’s hard to see how ChatGPT could make things worse. If you’re satisfied with cranking the handle of the copy-and-paste machine, you have no reason to look down your nose at ChatGPT.” Ken cites to similar sentiments from Andrew Stokes:

If we acknowledge the empirical reality of our current copy-and-paste culture, it is straightforward enough to project a few ways LLMs might improve on the status quo without fundamentally transforming it:

-

LLMs prove to be better and/or faster at copy-and-paste to arrive at suboptimal first drafts

-

LLMs shift expectations around automated drafting, leading to more investment in, and greater utilization of, good knowledge management practices, including templates

-

LLMs augment good knowledge management practices—e.g., faster production of templates, more consistent application of playbooks—in a manner that does not remove the human expert at the helm

And maybe, someday, an LLM will be used to apply the sixth edition of Ken’s MSCD to every contract destined for EDGAR (yes, generative output can be programmed to conform to a style guide; as part of the CoCounsel unveil on MSNBC, Greg Sisskind, who is utilizing CoCounsel on a pro bono class action on behalf of Ukranian refugees, talked about uploading his own 3,000 page manual and using CoCounsel to ask his own writing questions).

Addressing the robot lawyer elephant in the room. Having a machine produce an initial draft of a contract or legal opinion for a partner to edit sure sounds like something junior lawyers currently do—except the machines operate at warp speed.

I do not care.

First, the law does not exist to keep lawyers gainfully employed, let alone ensure we do the same things the same way, forever. If technology-assisted review provides litigants more accurate answers, faster, at lower cost—which it has since at least 2005—I am unmoved by the historical fact that many clients have paid many lawyers many dollars to manually review every last irrelevant document, instead of concentrating their attention on the relevant ones.

Second, I am a broken record that compounding legal complexity only makes expert legal guidance more valuable. There is not only latent demand in PeopleLaw (a broader view on our perpetual A2J crisis) but large corporations are also accumulating operational risk due to the evolving challenges of navigating an increasingly law-thick world. See receipt, receipt, receipt.

I am not the least bit persuaded that lawyer roles as trusted advisor and advocate are under threat. I am beyond persuaded that many legal needs go unmet. I am fundamentally concerned with our ability to lawyer at scale. Core to LexFusion’s Second Annual Legal Market Year in Review was a challenge to law departments and law firms to "calculate what percentage of their total spend is directed to projects that will progress their ability to deliver at scale—i.e., the leveraging of expertise through process and technology such that an increase in work does not require a proportionate increase in human labor."

Technology is fundamental to scale. Technology is also fundamental to us as humans.

For deeply personal reasons, I tend to characterize all humans engaging with our modern world as cyborgs. Unless you’ve gone full Kaczynski (and someone else has printed this out for you), you already are one and are likely becoming more intertwined with your tech over time. It is merely a matter of degree. When I first burst on the scene diatribing on the importance of technological competence, I was amused when lawyers would EMAIL me from their BLACKBERRY to lawyersplain to me how technology would never change how they practiced.

For deeply personal reasons, I tend to characterize all humans engaging with our modern world as cyborgs. Unless you’ve gone full Kaczynski (and someone else has printed this out for you), you already are one and are likely becoming more intertwined with your tech over time. It is merely a matter of degree. When I first burst on the scene diatribing on the importance of technological competence, I was amused when lawyers would EMAIL me from their BLACKBERRY to lawyersplain to me how technology would never change how they practiced.

Today, I need not need explain why a low-battery indicator should be accompanied by a trigger warning.

Cyborg is a personal preference. The likes of Damien Riehl are correct that the more accepted term is centaur. Whether cyborgs or centaurs, there is no lawyer vs robot divide. The collective challenge is augmenting and scaling human expertise in ways that, on net, improve client outcomes.

No one, however, has said it better than Steve Jobs and his “bicycle for the mind” (an often cited quote that is considerably more impactful in its original context).

Link to the above video

Jobs considered computers to be bicycles for the human mind. The original computers were the human mind.

This is happening. It will be done BY you or it will be done TO you. Computer was once an occupation, like lawyer or accountant. Computers were people.

This is happening. It will be done BY you or it will be done TO you. Computer was once an occupation, like lawyer or accountant. Computers were people.

Human computers performed labor-intensive calculations. They made invaluable contributions to the advancement of science and technology (e.g., Katherine Johnson). As silicon exceeded carbon in executing brute-force calculations, human computers became the first programmers—since most human computers were women, so, too, were the earliest programmers; another “omission of women from the history of computer science.”

The machines took some jobs. But they created more jobs than they destroyed. And facility with math became more valuable. Advancements in science and technology accelerated while finance, business, and law shifted towards being increasingly data driven.

While I do not think lawyer as an occupation is in any danger, I expect some roles to change dramatically—slowly at first, and then suddenly (like going bankrupt).

Consider a corporate contracting workflow that is operating near Level 3 automation.

-

The business user interacts with the chat bot to request and produce a contract for a counterparty (think Josef).

-

If the business user does not have full authority, the contract is routed for proper approvals. Instead of reviewing the contract itself, the approvers review the accompanying automated summary thereof (think Tome).

-

Upon authorization, the contract is sent to the counterparty. The contract is automatically reviewed against the counterparty’s playbook and market (think Blackboiler, LexCheck, TermScout).

-

Any edits are returned automatically (think Lynn). At which point the original party’s own automated comparison to playbook kicks in. The systems exchange drafts until agreement is reached.

-

If agreement is not reached because no fallback positions are mutually acceptable, the points of contention are escalated to humans (think ndaOk): business professionals if business terms; legal professionals if legal language.

-

When the draft is finalized, the contract is automatically signed [I suspect we hold off on this one for a bit] and circulated (think PandaDoc), accompanied by a digestible summary (#2).

-

The contract is automatically routed to a repository and all contract data is extracted not only for tracking, reporting, analytics, and queries (think Cognizer) but also to be piped into the appropriate enterprise systems (think Connected Experience).

- Contract data includes data about the contracting process itself so the process can be refined to drive better business outcomes. Status. Backlog. Velocity. Volume. Number of turns. Frequency of specific fallbacks. Frequency of, and triggers for, human intervention, and the impact thereof. Et cetera.

There is far less for a lawyer to do in the above scenario than a still-too-common workflow where the business user requests a contract via email and then the lawyer does most of the work drafting, negotiating, redlining, and ensuring execution.

The current paradigm keeps lawyers busy. Too busy. In-house lawyers are so overwhelmed and burned out that 70% want to look for another job within the year. Law departments are trapped in an endless, impossible cycle of more with less. This is unsustainable. It is bad for lawyers. It is bad for law departments. It is bad for businesses.

The only escape is to stop organizing knowledge work the same way we organize physical work—with static roles permanently performing the same set of activities. Most knowledge work should be organized around projects. Knowledge projects should produce knowledge that can be embedded upstream in business processes—i.e., to achieve compliance by design through de-lawyering without de-legaling.

Lawyers remain instrumental to the success of such projects. The templates, clause libraries, and playbooks that make the foregoing scenario possible will not be produced by ChatGPT, even if a fit-to-purpose, LLM-powered application plays a strong supporting role. More effort can be redirected from 'doing' the work to 'improving' the work—e.g., reducing revenue leakage while increasing business velocity in the spirit of the WorldCC's contracting principles and their emphasis on commercial outcomes. Just as importantly, more finite lawyer time can be dedicated to the novel, high-end advice and counseling (what I refer to as embedded advisory) that is becoming increasingly business critical as the complexity of the operating environment compounds.

In my space, I do not consider any significant segment to be immediately at risk. But I predict, eventually, the greatest pressure will be experienced by law departments.

In-house teams have been growing at massive clip for decades. This growth is mostly predicated on savings via insourcing—essentially labor arbitrage. The most immediate savings have been delivered by insourcing high-volume, run-the-company work. The easiest work to insource is also the most amenable to automation.

Further, law departments are subject to the cost-based thinking that dominates many corporate conversations. The lack of precision and predictability in legal budgeting invites heightened scrutiny from finance. The resulting under-resourcing only feeds the business’s dim view of legal as the Dept of Slow and the Dept of No.

I do not anticipate the reinvigorated digital transformation teams from McKinsey, Bain, Accenture, the Big 4, et al. to base their updated sales pitch on shrinking the law department—legal spend is too small as a percentage of revenue. Rather, I expect them to sell the transformation of core business processes, like contracting, to improve outcomes and velocity while reducing labor costs. Some of the disintermediated labor will reside in the law department. The C-suite will consider this a feature, not a bug.

BigLaw will likely feel the pressure earlier—individual in-house lawyers can start asking after LLM deployment now, long before their own enterprise settles on, let alone implements, a strategy. While I do not consider this an existential crisis for most, I suspect the leapfrog potential of LLM-powered applications will only exacerbate the growing divide within BigLaw.

The premier firms are already organized around projects. They are not immune from technological advancement nor market forces. They will need to re-engineer how they work. But their value prop should endure—as will their profits.

Except, of course, re-engineering work in manner that reduces labor inputs while maintaining profitability suggests the billing model will need to change, or at least be updated. At some point, the model breaks if clients continue to insist on variants of the billable hour (yes, clients) while also insisting on the use of technology that materially reduces hours. Do we finally reach the AFA nirvana that so many have been predicting for decades? Or do we start introducing kludges to maintain some semblance of the status quo — e.g. a standard rate and substantially higher 'tech enabled' rate that puts the choice to clients as to how they expect their work to be done?

In these early days, there are more questions than answers. And firms reliant on core—rather than cream—mandates are probably in for a bumpier ride.

The need for service-model innovation will intensify. As a stop gap, I envision even greater exploration of captives (to offload the run work cost-effectively) and consulting (to help re-engineer the run work) because in-house teams will continue to have overflow while also struggling to reorient themselves under ever-increasing resource constraints—i.e., in-house under-resourcing extends to investments in process and technology.

Because service-model innovation is their origin story, I consider New Law well situated to both (i) offer immediate relief (process-oriented with lower labor costs) and (ii) gradually integrate & iterate the new tech into scalable systems. The only group seemingly better positioned are consultants—because many law departments and law firms will, understandably, have episodes where they are flailing.

Candidly, I am not sure what to advise law students. But with or without LLMs, I am convinced we must revamp our approach to training young lawyers (and seasoned lawyers, too).

Finally, it has been years since I spent real time in the small and solo space. I, however, have enough exposure, and have paid enough attention when Chas Rampenthal speaks, to be convinced we are in for a tidal wave of UPL inanity—with foolishness like the DoNotPay debacle providing ammunition to the wrong side of the debate (sidenote: do not trifle with Kathryn Tewson is a classic blunder, ranking right up there with never get involved in a land war in Asia).

How to evaluate LLM-powered products. Speaking of DoNotPay, it represents the extreme end of the nonsense spectrum with respect to introducing LLMs into legal service delivery. "Robot lawyer" should be an immediate red flag no matter how potent the clickbait.

At the other end of the spectrum is Docket Alarm announcing the incorporation of GPT 3.5 to summarize filings. This is a task for which the model is well suited, with errors being both low likelihood and low consequence. It introduces a net new feature that would have been cost prohibitive absent a tech-based solution (i.e., human editors were not summarizing 550M documents). As Damien Riehl of Fastcase/Docket Alarm observed in his post on centaurs, we should interrogate all tools, not just tools incorporating LLMs, on an Efficacy-Cost Matrix.

At the other end of the spectrum is Docket Alarm announcing the incorporation of GPT 3.5 to summarize filings. This is a task for which the model is well suited, with errors being both low likelihood and low consequence. It introduces a net new feature that would have been cost prohibitive absent a tech-based solution (i.e., human editors were not summarizing 550M documents). As Damien Riehl of Fastcase/Docket Alarm observed in his post on centaurs, we should interrogate all tools, not just tools incorporating LLMs, on an Efficacy-Cost Matrix.

Tools are tools. Tools should be evaluated on the merits for problem/solution fit. None of my bullishness on LLMs obviates my prior warnings about the dangers of tech-first solutioning. In between the extremes of dumb publicity stunt and small, useful feature is the inconvenient truth that LLMs will not solve the challenge of properly appraising tools that incorporate LLMs.

I am confident there will be many worthwhile LLM-powered applications in legal. Parallel Search, AllSearch, and CoCounsel are evidence of that. I am just as confident there will be many less-than-worthwhile applications riding the LLM hype train. I am certain distinguishing the former from the latter will require work (choice overload will increase, as will the premium on trust). I am equally certain that even good tools will be misapplied because of failures to do the prerequisite process mapping, stakeholder engagement, future-state planning, and requirements gathering, not to mention process re-engineering, implementation, integrations, knowledge management, change management, and training. LLMs will change much. But LLMs will not change everything, and the danger of automating dysfunction remains high.

I am a cautious optimist. I’ve never been more excited about what’s possible. I’ve never been more pre-annoyed at how much nonsense is about to be unleashed. It will be fun. It will also be not fun. Most of all, to channel my cherished friend Jason Barnwell, I am convinced things will get weird.

Very weird. Indeed, I feel parochial and pedantic to focus on the legal market given the far-reaching implications of this moment. Thus, to end with a bit more flavor, a few artifacts from deep in the uncanny valley, proving hallucination can be world altering:

-

An AI-generated podcast between Joe Rogan and Steve Jobs that never happened but now exists

-

An AI redubbing that makes real actors say things they never said in languages they do not speak

-

"This is not Morgan Freeman" starring not Morgan Freeman as Morgan Freeman welcoming us to our new synthetic reality